How do we practice a socially just science? Join Free Radicals, a Los Angeles-based feminist and anti-racist community organization of scientists, that aims to incorporate a critical social justice lens into science, for an interactive workshop on feminist practices and socially conscious frameworks for building feminist research and engineering practices. Justice provides a framework for scientists to think through the hidden assumptions in their methodological approaches, and challenges researchers to think more deeply about the political implications of their work.

Participants will be challenged to apply principles and practices of justice to their own work, interrogating questions such as: Who benefits? Who is harmed? Who is most vulnerable?

In our communities of practice and beyond, whose well-being are we responsible for? How do our individual and collective identities affect the questions we ask? And ultimately, who do we do science for, and why? The workshop will conclude with practical skills and resources for participants to push their research communities to be more inclusive, equitable and attentive to social justice.

Free Radicals is a collective that envisions an open and responsible science that works toward progressive social change. Our work focuses on creating resources for political education through workshops and our blog: freerads.org.

Paloma Medina is a second year Ph.D. student in Biomolecular Engineering and Bioinformatics (UCSC) studying genetic ancestry and the evolution of sex. She has worked with the science of de-extinction, developmental biology, and animal behavior. As part of the Science and Justice Research Center Training Program, she helped initiate the Queer Ecologies Research Cluster and is continually seeking new creative ways to promote biodiversity. More information about Queer Ecologies can be found at: https://users.soe.ucsc.edu/~pmedina/queer_ecology_reading_list.html.

Co-Sponsored by the UC Santa Cruz Initiative for Maximizing Student Development (IMSD), Institute for Scientist and Engineer Educators (ISEE), Women in Science and Engineering (WiSE)

Wednesday, January 31, 2018 | 4:00-6:00 PM |Engineering 2, room 599

Event Description

Event description by Bradley Jin

Paloma Medina and Free Radicals pose with SJRC's Jenny Reardon and Karen Barad. Photo credit: Bradley Jin.

In a packed room in the E2 building at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Paloma Medina stood before an attentive audience. She spoke about why she loves biology. For her, biology is a way to redefine the word ‘natural.’ To many, what is ‘natural’ is the difference between right and wrong, normal and abnormal. She finds this definition lacking; it does not reflect the diversity of people and things that she sees every day. Medina wanted to find a new, better ‘natural.’ To do this, she had to take a journey of self-reflection. Through careful consideration and thought, she found what she was looking for: feminist science.

Medina wants to share feminist science with others. To help others practice feminist science, she, along with the Free Radicals, hosted Research Justice 101: Tools for Feminist Science. On a cool February afternoon, faculty, professors, and graduate and undergraduate students alike came together to learn about and discuss feminist science—what it is, and why we need it. Medina focused on the uses of reflexivity, critical theory, and feminist standpoint theory in her work. She and the Free Radicals asked the audience to consider how communities, cultures, and historical locations all factor into the viewpoints from which they interpret the world. By interrogating where we stand, we can better understand what assumptions we bring to scientific inquiry. Participants divided into pairs to try to apply this to their own research, as well as to each other. Each pair discussed their current research or research aims. Attendees asked each other how, why, and for whom their research existed: Is it accessible? What will it be used for? Attendees considered these questions and more.

Each pairing then assembled together to form larger discussion groups. Each group was led by a faculty advisor as well as a member of the Free Radicals. Groups collaborated to explore ways in which they could practice feminist science. Each group produced something different. Some spoke about how to communicate feminist science to the public, while others discussed how to redefine objectivity. At the end, the groups came together and shared what they had learned.

The event concluded with a request: Medina and the Free Radicals asked the audience to not only leave with a better understanding of feminist science, but to actually commit to practicing it. In unison, the audience shouted out what they would do to to make their science better. Some pledged to talk to colleagues or friends about feminist science. Others promised to make sure that their research was accessible and not hidden behind academic paywalls, or to remain conscious of their social and economic status so that they wouldn’t undervalue their privileged positions. The attendees left with both a new set of tools for practicing feminist science and a renewed sense of purpose.

Rapporteur Report

Critical Listener and Rapporteur Report by Dennis Browe

Convener: Paloma Medina

Participants:

Free Radicals, a “Los Angeles-based feminist and anti-racist community organization of scientists, that aims to incorporate a critical social justice lens into science.”

- Sasha Karapetrova, laboratory assistant and prospective environmental science/biochemistry graduate student

- Alexis Takahashi, multiracial community organizer, garden educator, and writer.

- Linus Kuo, market researcher with a background in psychology, and current Masters of education student.

- Andy Su, aspiring science educator and seeking to translate his experiences in community organizing toward transforming science institutions.

- Paloma Medina, Ph.D. student in Biomolecular Engineering and Bioinformatics (UCSC) studying genetic ancestry and the evolution of sex.

Overview

The overall goal of this workshop was to introduce – and collectively think through – various tools for scientists from a range of disciplines to grapple with questions of justice in their research. The Free Radicals use feminist science studies as a guiding frame to grapple with these questions. Amidst upbeat music playing overhead, the workshop began within a warm and welcoming atmosphere. Soon the room was overflowing. By the start of the welcoming commentary participants lined the back and side walls. About forty participants were gathered, and an informal audience poll showed that there was a wide mix of people in the room – professors, graduate students, undergraduates, and some staff and community members, comprising a variety of backgrounds and disciplines spanning the computer, physical, natural and social sciences and the humanities – a perfect mix for the themes of this workshop.

Jenny Reardon (UCSC Professor of Sociology and SJRC Director) gave a brief welcome, happily acknowledging, with assent from the crowd: “I think we can conclude there is an interest in research justice on this campus.” Dr. Reardon then introduced Kate Darling (former SJRC Associate Director and UCSC Sociology adjunct faculty), who helped to further set the tone of the afternoon: “We don’t necessarily want to retreat from a move where we protect science, or only critique it, but to open up conversations of justice and equity in STEM fields, in health research and care.” Dr. Darling then introduced the Free Radicals team to begin the workshop, which took the form of an interactive presentation (using Powerpoint on a large screen) interspersed with three participatory activities – individual, pairs, and larger groups, all focusing around locating participants’ own research projects and interrogating various assumptions and power dynamics built into these projects.

POLITICAL ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Sasha Karapetrova, a Free Radical, began with a political acknowledgment of the context in which the event was taking place: “We are gathered here and doing this workshop on the occupied lands of the Amah mutsun Tribe.” Sasha then asked the room: “Is research just?” Almost no one raised their hand. She then asked if people think research is unjust. To this question there was a more varied response – some thought yes, some no, and others mentioned that they have mixed answers here. This helped situate the room further, illustrating that many attending this workshop share some overlapping concerns regarding justice and injustice in research. Here the workshop was still speaking of these issues at a high level, without delving into the specifics of how each might play out in more concrete practices, i.e. what are injustices participants encounter or notice in their own research and institutions, and what strategies they have pursued to attempt to rectify these issues.

EXAMPLES OF UNJUST SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

The Free Radicals team then launched into the main presentation, each team member stepping in and out, collaboratively taking turns leading various parts of the slideshow. They began by covering ways in which research can be unjust: science employed by the State or military can damage the land (such as DDT research and use); the process of conducting unethical experiments (such as the infamous Tuskegee syphilis case); and, third, ways that science is done, such as larger budgets into research for cystic fibrosis compared to sickle cell disease[PM1] .

THE FEMINIST SCIENTIFIC METHOD

The team moved onto discussing the scientific method, stating that this method or framework does not leave much room for scientists to interrogate their own process of research. They discussed the “God trick,” one assumption of science in which scientific research creates an illusion of pure objectivity (referencing Donna Haraway’s 1988 article on “Situated Knowledges”). The team explained that to move away from this “God trick” we need to embrace a feminist science, using tools from multiple theoretical lineages including feminist standpoint theory (Smith 1997, Harding 2004, Collins 1997, Haraway 1988) and feminist intersectionality (Crenshaw 1991). The team further cited Dr. Deboleena Roy’s “Feminist theory in science: working toward a practical transformation” as a feminist model of inquiry, helping to put theory into practice. They stated that through using these feminist frameworks, science can and should benefit marginalized communities and challenge power and knowledge dynamics: working from these different assumptions could, ideally, help result in research justice.

LOCATING YOURSELF, THE FIRST STEP TOWARDS RESEARCH JUSTICE

The Free Radicals began detailing the steps of how to do research with questions of justice remaining at the forefront, starting with locating oneself, the communities one comes from and lives in, and one’s historical and cultural locatedness. Questions of locatedness demonstrate how knowledge and knowledge-making is socially and historically situated. One participant asked for the team to distinguish between cultural and community. The team members helped each other out, answering that we can think of cultural as about broader norms in a society, versus more specific community norms we are a part of. Paloma, the Convener, helped illustrate these points by discussing her own research. She located her own background, describing her multiple identities as a queer woman of color and as a biologist. She explained how her locatedness has sparked her research goals, beginning to explore what is the “natural.” She thus applied her skills in biology to study sex chromosomes and their naturally occurring mutations in various species.

LOCATING YOUR RESEARCH

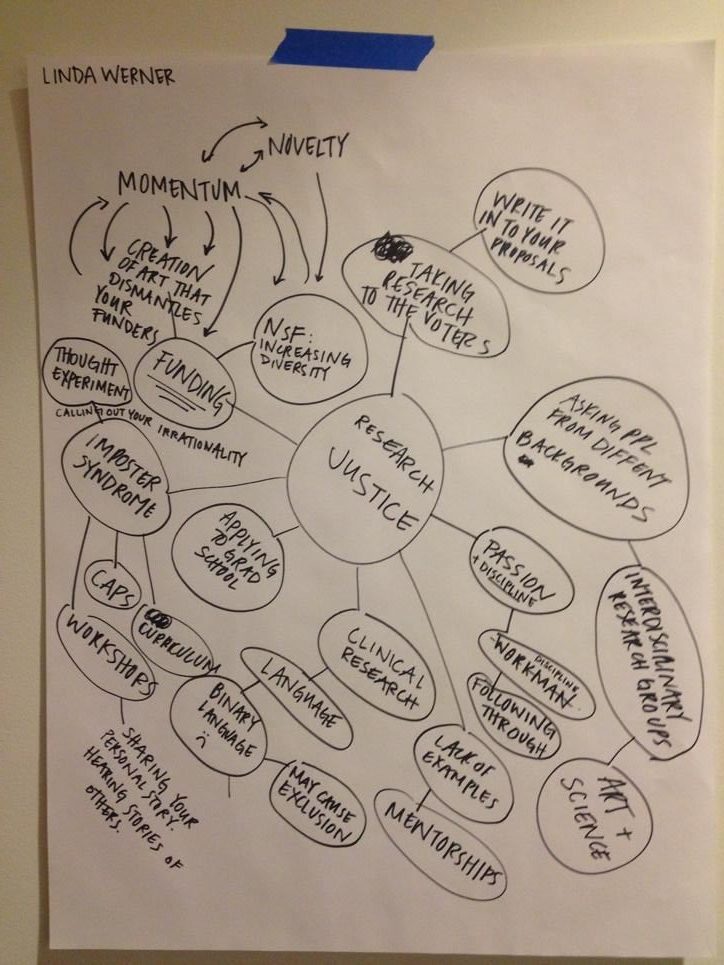

After doing an individual activity on “Locating your Research,” the Free Radicals introduced a simultaneously useful and humorous (for its overwhelming number of nodes) mindmap on the big screen – a chart borrowed from Charlotte Cooper on “Research Justice: Some Handy Questions.” They then led the room through the steps of thinking through a research project with a feminist lens: after locating one’s research, define the purpose and clarify the questions one is asking; then interrogate the hypothesis, meaning asking questions such as “how was the research done and who designed it? Who participated, and how?” The final step is to analyze power dynamics of the completed research – how was it disseminated? What was done afterwards? The relationship between the scientist and the subjects of the research must be recognized and articulated. The team mentioned the importance of turning to an interdisciplinary range of knowledge and theories for explanations and forms of evidence.

GROUP ACTIVITY: TRANSFORMATION

For the final third of the workshop, the Free Radicals led a large-group activity. The activity involved participants splitting into five groups of seven with each Free Radical pairing with a professor in the room to co-lead their group. The task was to brainstorm how to transform institutions to more thoroughly include research justice and how to create strategies for social change (Figure 1). During report-back, one strategy discussed amongst the room is finding out where the momentum in funding sources currently is. One can figure out how their own research interests relate to the momentum of the already built research field/institution. Additionally, one can create a niche for their research, and build out community and ideally obtain funding toward researching this niche interest. A few participants expressed being uncomfortable letting personal passions drive their research for fear of it discrediting their research. By voicing concerns and hurdles met when applying the feminist model of inquiry, many strategies to overcome barriers to research justice were shared among the group. It is clear that discussions and events that center research justice strategies, potentially a grant writing workshop, are desired and needed to help researchers

Figure 1. Photo of group activity brainstorm led by Professor Linda Werner, Computer Science, and Paloma Medina, Biomolecular Engineering.

GROUP ACTIVITY: SEMANTICS OF ‘FEMINIST’ SCIENCE

One question that came up during the group activity, which offers occasion for citizen-scientist groups such as the Free Radicals and SJRC to continually interrogate (because there is no final, perfect answer to arrive at) is the semantics and definitions used toward building justice in research practices. One participant commented that they understand issues of justice to be a daily concern in running a lab and research projects, yet do not understand why a specifically “feminist” lens is needed. They work in a lab led by a woman of color and see her daily handle practical issues – bureaucracy, funding stretched thin, implicit and structural issues of racism and sexism – that tend to impede on her and her lab’s ability to more fully tackle issues of justice and inclusivity, such as training more young women of color scientists. These same practices might be termed “feminist” by some, but not by others, and a question becomes, do these semantic distinctions make a difference, and if so, what differences might they make?

GROUP ACTIVITY: SCIENTISTS NEED TO SHOW UP

The team spoke of encouraging scientists to “show up” as much as possible, to try and get communities to care and to foster citizen scientists from the community, while acknowledging that scientists need to be citizens too. A participant remarked that ethics within science is generally too narrow a framework for thinking about issues of inequality and equity; instead, questions of justice probe deeper than ethical legal frameworks for the scientific research being done. A further strategy discussed is how to diplomatically connect departments, such as life scientists, physicists, computer scientists, and/or engineers coming together with social scientists and humanities scholars. These themes clearly overlap and resonate with the mission of the Science and Justice Research Center, and this workshop proved to be a valuable encounter for furthering this mission. By bringing together a wide range of participants –in terms of both career-stage and disciplinary backgrounds – it helped foster a shared framework for thinking through concrete ways to put these goals into action.

CONCLUSIONS: FRAMEWORK OF CHANGE

The Free Radicals ended the workshop by briefly touching on the “Ecological Framework of Change” for doing feminist science and research: a diagram consisting of concentric circles, representing different levels at which change can be fostered: the individual is the innermost point or circle, surrounded by a working group, surrounded by an institution, which is lastly enveloped within a field of study. Before participants left, each person was also given an artistic postcard to take home with them, to write down an action that they could commit to taking as a result of coming to the workshop. These gestures provided a fitting linking of this ending to serve as a new point of departure for projects bringing together a range of scientists and humanists, academics and citizens, to continually build community in the interests of justice in science and research more broadly. Commonsensical in some ways, justice in research should never be a singularly taken-for-granted category, goal, or strategy for change. Through hosting future events, the Science & Justice Research Center can and will continue interrogating meanings of research justice and its promises offered of a better world, or worlds.

Works Cited

Collins, Patricia Hill. "Comment on Hekman's 'Truth and Method: Feminist Standpoint Theory

Revisited': Where's the Power?" Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society22.2 (1997): 375-381.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. "Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color." Stanford law review (1991): 1241-1299.

Haraway, Donna. "Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective." Feminist studies 14.3 (1988): 575-599.

Roy, Deboleena. "Feminist theory in science: working toward a practical transformation." Hypatia 19.1 (2004): 255-279.

Smith, Dorothy E. "Comment on Hekman's 'Truth and Method: Feminist Standpoint Theory Revisited'." Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 22.2 (1997): 392-398.