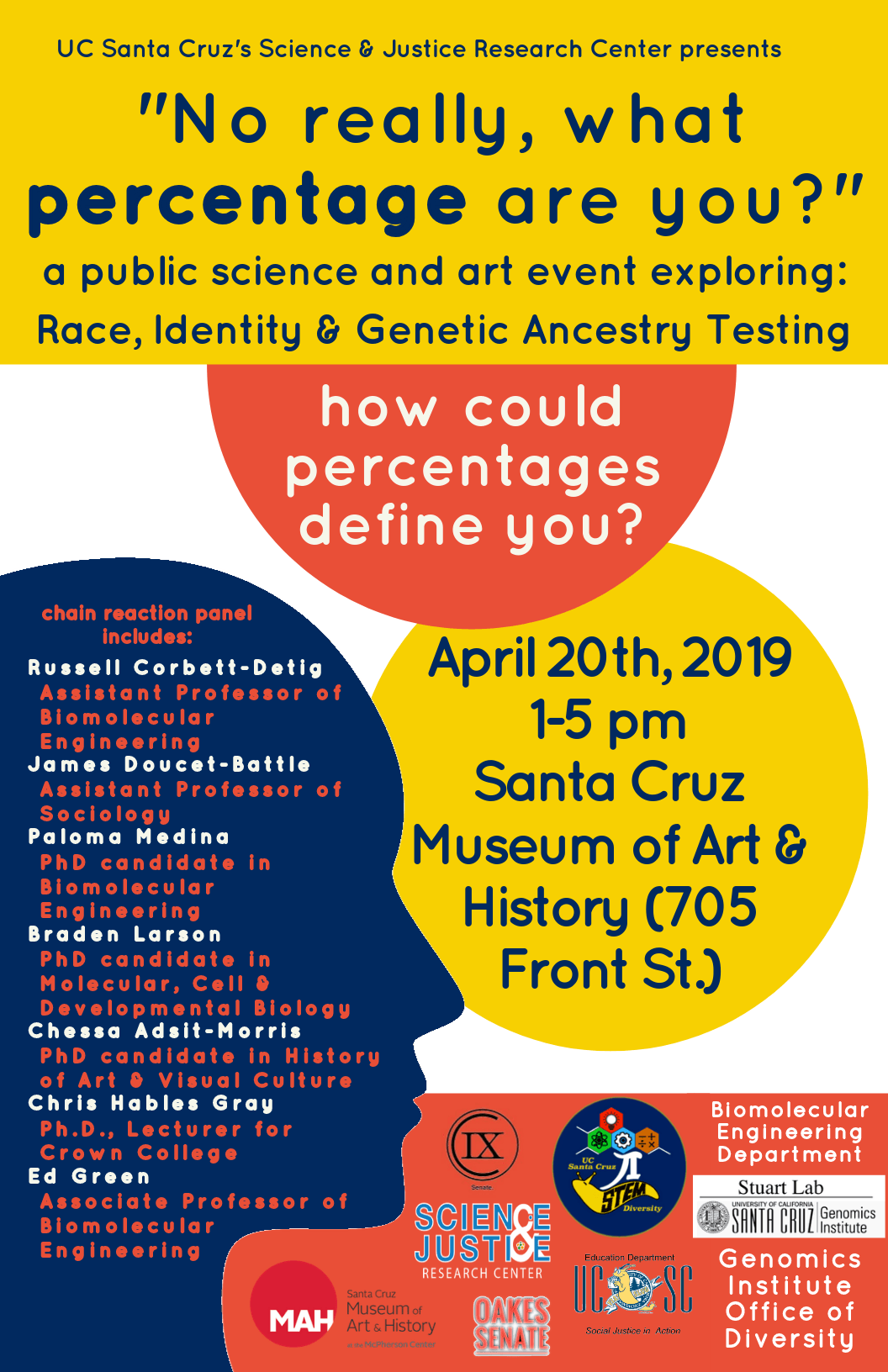

Saturday, April 20, 2019

1:00-5:00pm

Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History (705 Front St. Santa Cruz)

Free and open to the public; refreshments provided; no registration needed

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing services such as 23andMe and Ancestry.com are rapidly becoming a cultural touchstone, a mainstream phenomenon with significant implications for common notions of race and ethnicity, personal and social identity. Our public event will explore the promises and the problems of DTC genetic testing services, under the broader umbrella of racial justice and genomics.

We will explore questions arising within this new landscape of public genomics: How are people integrating genealogical knowledge (such as of their family tree) with new forms of DNA-based ancestry testing? What is the relationship between our genetic makeup and our racial and ethnic identities (and the ways we are racially classified)? What kinds of genetic ‘truths’ are being produced by these forms of commercialized science? Further, who owns, and has access to, our genetic data? What kinds of organizations are using our data, and for what purposes?

We will explore questions arising within this new landscape of public genomics: How are people integrating genealogical knowledge (such as of their family tree) with new forms of DNA-based ancestry testing? What is the relationship between our genetic makeup and our racial and ethnic identities (and the ways we are racially classified)? What kinds of genetic ‘truths’ are being produced by these forms of commercialized science? Further, who owns, and has access to, our genetic data? What kinds of organizations are using our data, and for what purposes?

We will engage both science and art to creatively grapple with questions of race and ethnicity in this age of data-driven identities. Our event will host an art exhibit on genomics and identity; an interactive collage-making session; and an experimental type of panel called a chain reaction in which professors and graduate students working in this broad field will converse in a semi-structured conversation through a chain of dyads.

Hosted by Science & Justice Training Program Fellows:

Jon Akutagawa (Biomolecular Engineering), Dennis Browe (Sociology), Maggie Edge (Literature), Dorothy R. Santos (Film & Digital Media) and Caroline Spurgin (Education) with undergraduate fellow Diana Sernas (Mathematics).

If you feel that genetic ancestry testing has benefited or impacted you in some way, please inquire and send anecdotes to Dennis Browe.

Participants:

Chessa Adsit-Morris, UC Santa Cruz Graduate Student of History of Art & Visual Culture

Russ Corbett-Detig, UC Santa Cruz Assistant Professor of Biomolecular Engineering

James Doucet-Battle, UC Santa Cruz Assistant Professor of Sociology

Ed Green, UC Santa Cruz Associate Professor of Biomolecular Engineering

Chris Hables Gray, Lecturer, UC Santa Cruz Crown College

Braden Larson, UC Santa Cruz Graduate Student of Molecular, Cell, & Developmental Biology

Paloma Medina, UC Santa Cruz Graduate Student of Biomolecular Engineering, Science & Justice Fellow

Co-Sponsored by

The UC Santa Cruz Science & Justice Research Center, the School of Engineering NIH Training Grant, College Nine Student Senate, the departments of Biomolecular Engineering, Education, and the Genomics Institute Office of Diversity, Oakes College Senate, and the Stuart Lab.

Rapporteurs’ Report

Introduction

With the human genome first sequenced and reported in 2001 and then a final draft in 2003 – the end-goal of the Human Genome Project (HGP) – some scholars now term this post-HGP era as one of ‘postgenomics.’ (Reardon 2017; Richardson and Stevens 2015). In this postgenomic era, questions of race and ethnicity are at the forefront of both scientific debates and popular cultural movements: the recent controversy over Harvard geneticist David Reich’s New York Times op-ed in March, 2018 has scholars publicly debating the usefulness of racial categories as precise forms of scientific analysis; the public return of white nationalism(s) across many countries; as well as the use of forensic genetics to solve crimes, the growth of DNA ‘magic boxes’ in police stations, and the raising of concerns about discrimination in DNA phenotyping.

On the level of ‘personal genomics,’ direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing services such as 23andMe and Ancestry.com are rapidly growing into a mainstream phenomenon. They have arguably become a cultural touchstone, with significant implications for common notions of race and ethnicity, personal and social identity. The tools of genetic ancestry testing are increasingly being used for myriad projects of adjudicating one’s identity, such as conceptualizing racial/ethnic heritage as percentage points of ancestry. For example, many in the US now hope to find ‘Native DNA’ to believe they are members of a tribal nation, while tribes do not simply recognize blood quanta as the primary marker of tribal belonging (TallBear 2013); white supremacists are chugging milk; and African Americans are using personal genomics to construct meaningful biographical narratives, engaging in what Alondra Nelson terms ‘affiliative’ self-fashioning in the context of their genealogical aspirations (2016).

To grapple with the implications of some of these world-making projects, our event “No, Really, What Percentage are You?”: Race, Identity, and Genetic Ancestry Testing, explored the promises and the problems of DTC genetic testing services, under the broader umbrella of racial justice and genomics. Over the course of a 4-hour event held at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History on April 20th, over 120 community members joined the fellows along with guest panelists to explore how both science and art engage questions of race and ethnicity that are so prevalent today in this age of data-driven identities. The primary questions explored were as follows:

- How are people integrating genealogical knowledge (such as of their family tree) with new forms of DNA-based ancestry testing?

- Is mapping one’s genetic ancestry an act of restoring the past, or does granting a private company access to this information encourage us to commercialize our own genes, or some combination of both?

- Does it act to uphold existing concepts of race through ancestry, or can it encourage people to see categories as being more flexible than previously thought?

- Who benefits from these projects, and who might be harmed?

Event Activities and Outcomes

To explore these questions through various activities employing science and art, our event unfolded across two areas of the museum — the main atrium and small conference room (seated, approximately 50) — and featured a number of main attractions: 1) an art installation showcasing the work of artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg; 2) an experimental conversational panel called a chain reaction; 3) large educational posters covering aspects of the foundational concepts and science behind genetic ancestry testing; 4) a collaborative art-making and collage station; 5) and a curated playlist of videos about genetic ancestry testing. We detail each of these activities below.

1) Art Installation

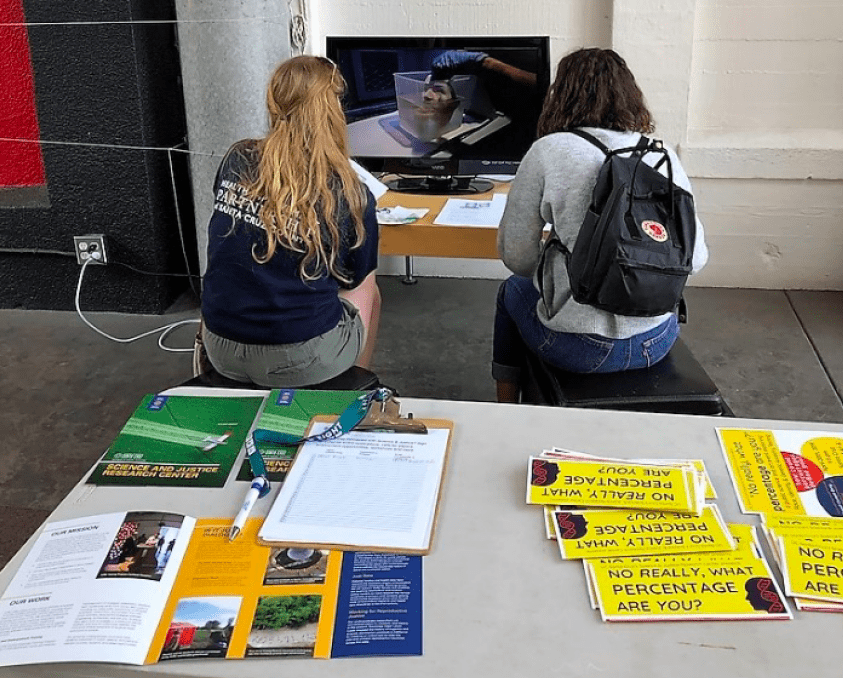

Two artworks were shown close to the museum entrance and near the event’s welcome table in the atrium. Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s video work, Stranger Visions, along with a zine she co-created with Chelsea Manning and Shoili Kanungo titled Suppressed Images, were shown as a pop-up solo show. The artworks showed the process the artist performed to create 3D printed sculptures from DNA sequencing and phenotyping processes. Through this work she raises concerns about the impulse genetic determinism and the biases and limitations of these DNA phenotyping processes. Event participants displayed curiosity toward this forensic process and the critical (and critically important) questions raised by this video-artwork.

2) Chain Reaction Panel

The chain reaction is an experimental take on the panel discussion format. Seven experts served as panel participants (see below). Dyads were in conversation for approximately 12 minutes each. The format was as follows: the first and second speakers engaged in an initial semi-structured conversation on pre-selected topics for 12 minutes. Once the first conversation ended, expert 1 was asked to leave and was replaced by expert 3. Expert 2 and 3 continued the conversation for another 12 minutes. Then, expert 2 was replaced by expert 4. This process continued until all seven speakers spoke with two other speakers. Fellow Dorothy R. Santos served as the moderator for chain reaction.

True to the panelists’ diverse expertise, a wide range of topics were covered during this panel, ranging from the importance of narrative through the use of DTC genetic ancestry testing (both the use of cultural narratives as a marketing tool for these companies and the constructing of identity narratives through using the knowledge gained from these tests); who uses these tests and how they, as tools of identity-making, can be used toward many different ends and purposes; the history of genetics, replete with racism and eugenics; the question of gift exchange in our society and whether certain types of genetic gifts (such as agreeing to have one’s genome sequenced for the benefits of ‘science’) fall under sacrificial exchange or egalitarian forms of exchange; the appeal of DTC ‘personal genomics’ due to people’s striving for forms of certainty rather than uncertainty about their lives and identities; the technical possibilities for what DTC genetic ancestry tests can and cannot tell us, and with what levels of certainty, about our ancestry; histories of colonialism and genocide that must be taken into account when trying to paint accurate pictures of many people’s ancestries; and the ongoing question of improving technologies, such that we cannot necessarily predict how genomic information will be used in five and ten years from now — by whom, and toward what sorts of purposes and ends genomic knowledge will be employed.

In general, feedback on the chain reaction was positive, especially by the panelists who commented that they enjoyed the open-ended and stimulating conversation. Some audience members lamented the use of jargon by chain reaction participants–if we were to hold a similar event again in the future, we might consider working with chain reaction participants beforehand to help them think about communicating in more accessible ways.

3) Educational Posters

We hung four educational posters in the museum’s atrium, designed to break down complex scientific topics explored at our event.

The four posters covered: modelling genetic variation; racism and genetic science; beyond Mendellian inheritance; and inferring genetic ancestry. The posters provided a foundation to engage in conversation and that would result in an invitation to engage in the Collaborative Art Project. Event coordinators were able to spark interesting conversations by asking visitors (who were reading the posters) what they thought about different parts of the posters.

4) Collaborative Art Activity

The museum’s atrium served as a wonderful focal point for the collaborative art activity. With little to no verbal instruction, visitors gravitated to the art making table and began making collages answering two prompts. The following prompts were printed and displayed on the tables and the wall hanging for community members to respond to creatively:

“To quantify means to measure or express the quantity of something. For example, Genetic Ancestry Test results quantify your genetic ancestry. In two collages, show us how you would quantify yourself and the ways you cannot be quantified. Then add your collages to the wall to be part of the collaborative art project!”

Participants contributed their collages as responses to both the prompts and the educational posters hanging in the atrium. People of all ages were able to participate in the collaborative art activity.

5) Curated Video Playlist

In the small conference room, prior to the start of the chain reaction panel, short, accessible videos on genetic ancestry testing played on loop as visitors sat waiting for the panel to begin. Videos included a newly released educational video by Vox: What DNA ancestry tests can – and can’t – tell you; A provocative and satirical ad for AeroMexico Airlines for ticket discounts based on DNA test results; and informative, humorous videos, including one by BuzzFeedVideo: Ethnically Ambiguous People take a DNA Test; and a CBC News video called Twins get ‘mystifying’ DNA ancestry test results (Marketplace). The idea of curating the videos involved showing, first, a breakdown of the science involved, and second, some moral, ethical, and cultural questions raised around using DNA ancestry test results to rethink one’s ancestry.

Conclusion

This event served to engage the multi-layered discussion of genomics, race, and ancestry by providing students and the general public with the means and tools to become more informed and to think critically about this timely subject. We achieved our goal of facilitating an interdisciplinary discussion between art, science, and science education. We could also have had a more diverse range of experts on the panel since the majority were from the Biomolecular Engineering department. It may have been advantageous to include more social scientists and humanities scholars. This observation was made by a community member and the fellows made certain to listen to this visitor’s concern of lack of disciplinary diversity on the panel. Yet they, along with other visitors to the museum and students from the university, commented on the informative and engaging nature of the event. We realized after speaking with many event participants that we could have created a take-away bibliographic resource. We sparked the curiosity of many visitors and, we think, let people leave with many questions for further reflection, but we could have provided a more concrete list of relevant resources.

One line of future inquiry that arose from this event is the challenge of trying to understand the moral and ethical questions that are continuously arising as genomic technologies improve. As practices of DNA phenotyping are on the rise and the spectre of novel forms of genetic discrimination continues to haunt the fields of genetics and genomics, how can we, as members of a multitude of larger collectives, continue to ask relevant questions and remain pertinent in thinking through complex issues spanning science and race, identity and ethnicity, and the intertwining of genealogical and genetic ancestry?

References

Nelson, A. (2016). The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation After the Genome. Beacon Press.

Reardon, J. (2017). The Postgenomic Condition: Ethics, Justice and Knowledge After the Genome. University of Chicago Press.

Richardson, Sarah S. & Stevens, H. (2015). Postgenomics: Perspectives on Biology After the Genome. Duke University Press.

TallBear, K. (2013). Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. University of Minnesota Press.