Wednesday, October 16, 2019

2:00-4:00pm

Merrill Cultural Center

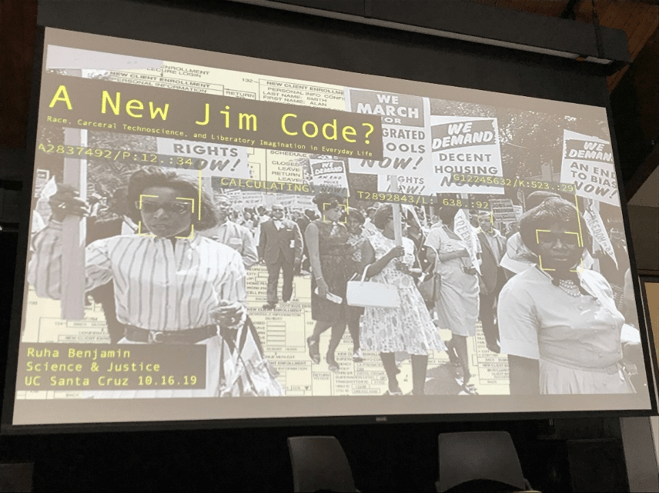

A New Jim Code? Race, Carceral Technoscience, and Liberatory Imagination in Everyday Life (PDF Flyer)

From everyday apps to complex algorithms, technology has the potential to hide, speed, and even deepen discrimination, while appearing neutral and even benevolent when compared to racist practices of a previous era. Benjamin will present the concept of the “New Jim Code” to explore a range of discriminatory designs that encode inequity: by explicitly amplifying racial hierarchies, by ignoring but thereby replicating social divisions, or by aiming to fix racial bias but ultimately doing quite the opposite. We will also consider how race itself is a kind of tool designed to stratify and sanctify social injustice and discuss how technology is and can be used toward liberatory ends. Benjamin will take us into the world of biased bots, altruistic algorithms, and their many entanglements, and provides conceptual tools to decode tech promises with sociologically informed skepticism. In doing so, it challenges us to question not only the technologies we are sold, but also the ones we manufacture ourselves.

Further reading:

Innovating inequity: If Race is a Technology, Postracialism is the Genius Bar

Black Afterlives Matter: Cultivating Kinfulness as Reproductive Justice

Ruha Benjamin is an Associate Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, where she studies the social dimensions of science, technology, and medicine. Ruha is the founder of the JUST DATA Lab and the author of two books, People’s Science (Stanford) and Race After Technology (Polity), and editor of Captivating Technology (Duke). Ruha writes, teaches, and speaks widely about the relationship between knowledge and power, race and citizenship, health and justice.

Q&A to be Moderated by SJRC’s Theorizing Race After Race cluster.

Co-Sponsored by Crown College.

Rapporteur Report by Dennis Browe

Ruha Benjamin, a sociologist and an Associate Professor in the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University, gave a lively presentation on the interconnections between race and technology and the great potential for  bias and discrimination that lies in algorithms and coding. Notably, Dr. Benjamin began not only with an acknowledgment of the indigenous tribal land that UC Santa Cruz is located on – the Uypi Tribe of the Awaswas Nation, represented today by the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band – but also acknowledged the intertwining legacies of the devastation of the transatlantic slave trade and settler colonialism. This was a fitting introduction to her talk, where she connected these devastating legacies to the ways in which current technologies and technological practices continue to reinforce – even inadvertently – these legacies of white supremacy through domination, both materially and at the level of the imagination.

bias and discrimination that lies in algorithms and coding. Notably, Dr. Benjamin began not only with an acknowledgment of the indigenous tribal land that UC Santa Cruz is located on – the Uypi Tribe of the Awaswas Nation, represented today by the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band – but also acknowledged the intertwining legacies of the devastation of the transatlantic slave trade and settler colonialism. This was a fitting introduction to her talk, where she connected these devastating legacies to the ways in which current technologies and technological practices continue to reinforce – even inadvertently – these legacies of white supremacy through domination, both materially and at the level of the imagination.

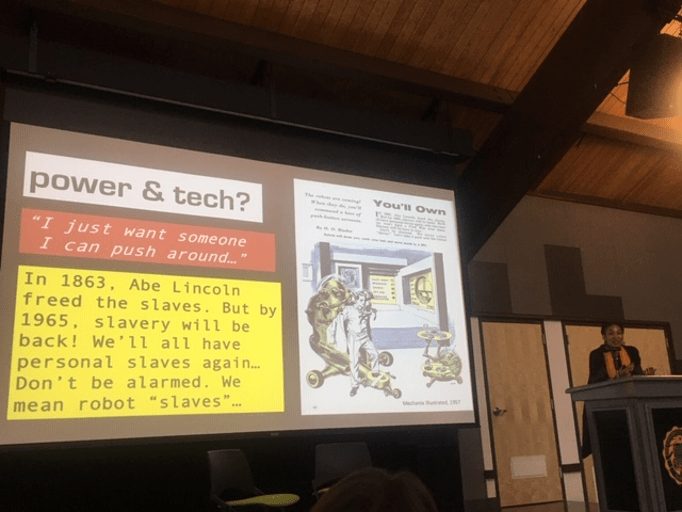

Dr. Benjamin made the case for how technology, which is presented as miraculous and imaginative, can actually be and often is used to subdue and subjugate people. She used three main contentions as the backbone of her presentation: 1) racism is productive, in the literal sense of its capacity to produce things; 2) racism is innovative: race and technology are co-produced, they shape one another, and social inputs that make some inventions appear inevitable and desirable are just as important as the social impact of technologies; and, 3) imagination is a contested field of action; it is not just an ephemeral afterthought, but an ongoing battleground for what becomes important to the social order.

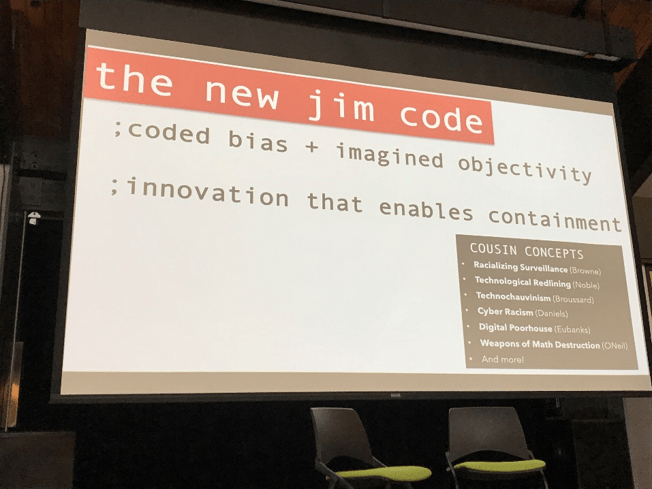

Covering a variety of media with implicit and explicit overtones of racial targeting and discrimination over the past seventy years, Dr. Benjamin illuminated how “technology captivates.” Riffing on Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, Dr. Benjamin sees “The New Jim Code” as a combination of coded bias and imagined objectivity: “Innovation that enables social containment, while appearing fairer than discriminatory practices of a previous era… this now entails a crucial sociotechnical component that not only hides the nature of domination, but allows it to penetrate every facet of social life under the guise of progress.” After detailing its features, she asked: why are techno-fixes so desirable? Noticing the absurdity of relaying on techno-fixes for working toward racial justice, such as ostensibly neutral resume review algorithms that HR departments are beginning to employ, she quipped, “If only there was a way to slay centuries of inequalities and oppressions with a social justice bot.”

We at the SJRC want to continue thinking through how Ruha Benjamin’s work, as a long-time friend and ally to SJRC, meshes with other recent events as they all converge around questions of advances in science and technology and the continual return to questions of race and racism. Race and racism seem to advance in lock-step with these developments even if, often, their optimistic promoters claim that these new technologies will do away with the need for racial characterizations or even race itself as a structuring social category. In April 2019, a team of SJRC graduate fellows hosted an event at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History named, “No Really, What Percentage are You?” Race, Identity & Genetic Ancestry Testing. At this event we interrogated the claims to neutrality and objectivity inherent in advertisements for direct-to-consumer genetic ancestry tests such those by as Ancestry.com and 23andMe. Through a variety of activities including a panel of professors and graduate students, a collage-making table, and an art exhibit, we similarly explored racialized assumptions embedded in the technology of genetic ancestry tests and the myriad ways that users make sense of their test results, including the creative ways they connect these results to their narrative of familial genealogy.

We at the SJRC want to continue thinking through how Ruha Benjamin’s work, as a long-time friend and ally to SJRC, meshes with other recent events as they all converge around questions of advances in science and technology and the continual return to questions of race and racism. Race and racism seem to advance in lock-step with these developments even if, often, their optimistic promoters claim that these new technologies will do away with the need for racial characterizations or even race itself as a structuring social category. In April 2019, a team of SJRC graduate fellows hosted an event at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History named, “No Really, What Percentage are You?” Race, Identity & Genetic Ancestry Testing. At this event we interrogated the claims to neutrality and objectivity inherent in advertisements for direct-to-consumer genetic ancestry tests such those by as Ancestry.com and 23andMe. Through a variety of activities including a panel of professors and graduate students, a collage-making table, and an art exhibit, we similarly explored racialized assumptions embedded in the technology of genetic ancestry tests and the myriad ways that users make sense of their test results, including the creative ways they connect these results to their narrative of familial genealogy.

One topic that surfaced during the panel discussion was that with the rapid advancement of genome sequencing technologies and computational biology, we cannot easily predict how genomic information will be taken up and used in five, let alone twenty years from now – by whom, and toward what sorts of purposes genomic knowledge will be employed. For example, we know that government units and police are already beginning to use forensic genomics to solve murder cases as well as to identify those moving through the criminal justice system. Dr. Benjamin’s work raises this same concern: with the rapid advancement of algorithmic technologies for automating more and more aspects of life, we cannot precisely determine the creative ways in which algorithms will be taken up in the near future. Admitting these limitations to predicting the future, how can frameworks for racial and gender-based justice be designed and, importantly, how can justice-based frameworks be implemented into the core design of new technologies, and not just as an afterthought?

Noting that this conversation about the ways in which racialized and often gendered assumptions become embedded in each new generation of technologies happens again and again (new techs; same concerns), Dr. Benjamin’s emphasis on the role of imagination offers at least one powerful way out of this cyclical trap. As she noted: most people are forced to live inside someone else’s imagination and we must come to grips with “how the nightmares that many people are forced to endure are the underside of elite fantasies about efficiency, profit, and social control.” Thus, not content to simply call out racializing and racist technologies, Dr. Benjamin ended by noting imaginative projects working toward tech & racial justice, including: Data for Black Lives; the Detroit community technology project; Science for the People; Tech Workers’ Coalition; and the Digital Defense Playbook. She stressed that we have to prioritize the proactive seeding of the world that we want – to save much of our energy for intellectual and political organizing, not just naming the problems.

With the proliferation and penetration of new technologies further into the mesh of everyday life, we must continue to ask these questions about the ways that racializing biases and outright discrimination become encoded into the hearts of new technologies, again and again. Following Dr. Benjamin’s lead, we, as a mix of social and natural scientists and engineers, must continue to make the case far and wide to intervene imaginatively. If so many are forced to live within other people’s imaginations, proactively imagining alternatives is one way to seed new presents and new futures. To end with an ongoing question: if the racializing biases embedded in new technologies will arise again and again, in what other ways can this problem be thought about and transformed at a systems level, rather than at a level of counteracting the discriminating effects of each new individual technology as it arises? Dr. Benjamin might have been thinking here not of seeding new trees individually, but of reimagining what the forest itself can be, how it can serve as a container for multiple, overlapping, aspirational forms of justice.