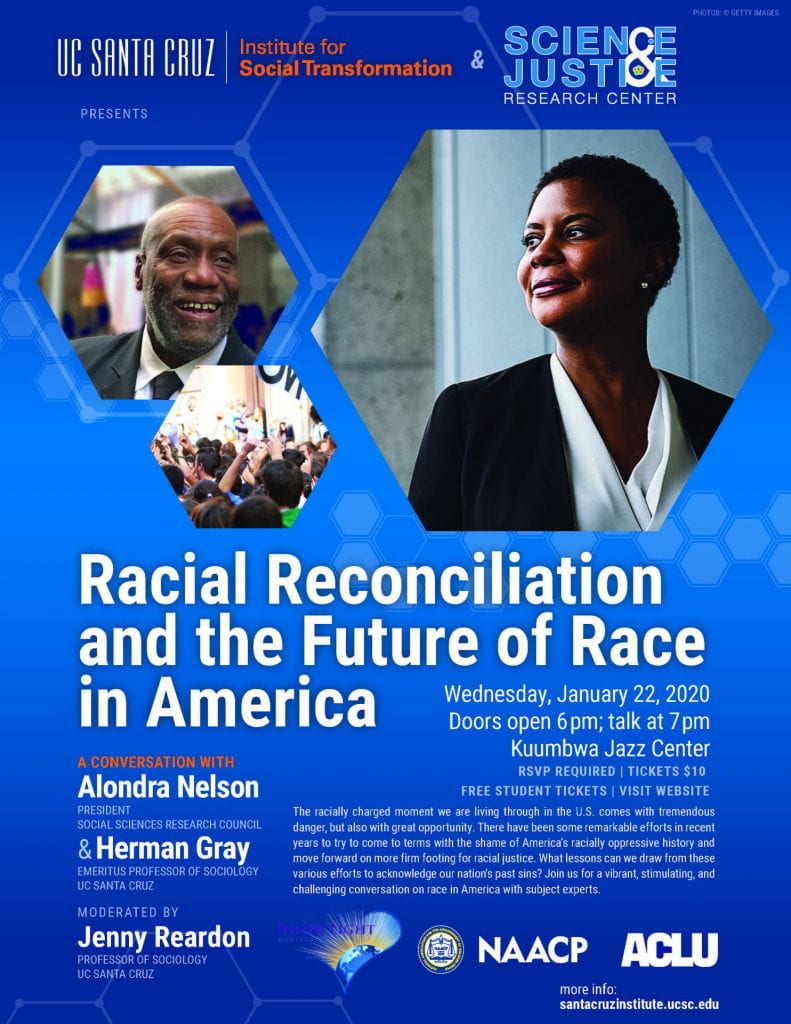

Wednesday, January 22, 2020

Doors opened at 6:00pm; talk began at 7:00pm

Kuumbwa Jazz Center (320 Cedar St, Downtown, Santa Cruz)

RSVP was required; tickets were $10 and a limited amount of free student tickets were made available.

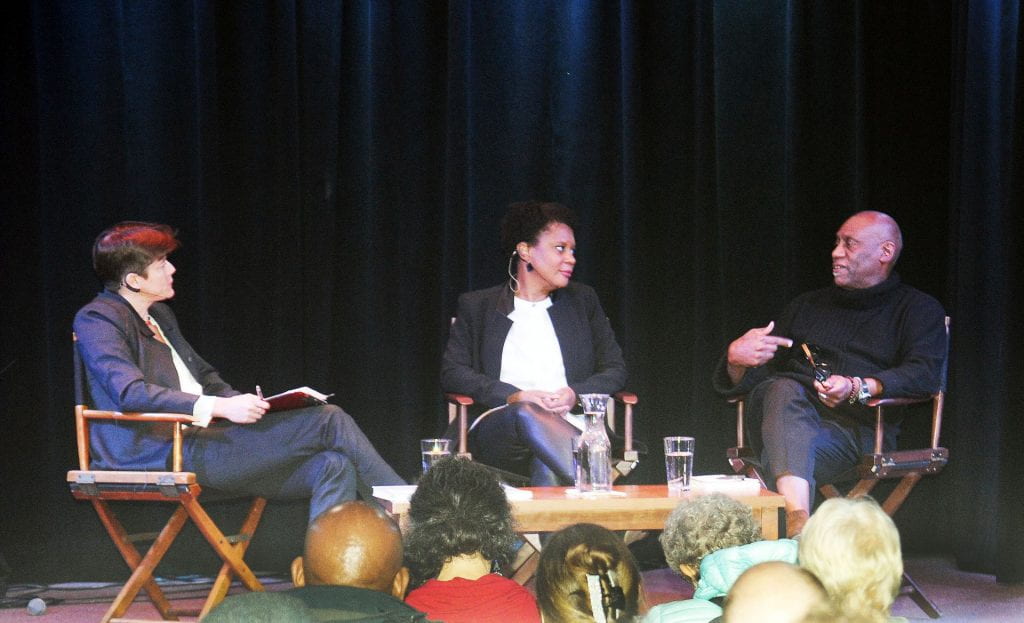

The community joined us for a vibrant, stimulating, and challenging conversation on race in America with Alondra Nelson (President, Social Sciences Research Council) and Herman Gray (Emeritus Professor of Sociology, UC Santa Cruz) as moderated by Jenny Reardon (Professor of Sociology and Director of the Science & Justice Research Center, UC Santa Cruz).

The community joined us for a vibrant, stimulating, and challenging conversation on race in America with Alondra Nelson (President, Social Sciences Research Council) and Herman Gray (Emeritus Professor of Sociology, UC Santa Cruz) as moderated by Jenny Reardon (Professor of Sociology and Director of the Science & Justice Research Center, UC Santa Cruz).

The racially charged moment we are living through in the U.S. comes with tremendous danger, but also with great opportunity. The dangers are obvious— blatantly racist statements by our president, the emboldenment of white supremacist movements, the rampant loss of black life at the hands of the police, the demonizing of immigrants, rampant Islamophobia and so on. Yet it is a time of tremendous opportunity—with the most racially diverse Congress ever, a diverse pool of Presidential candidates, growing national discussions about reparations for slavery, vibrant grassroots movements for racial justice emerging across the country. There have also been some remarkable efforts in recent years to try to come to terms with the shame of America’s racially oppressive history and move forward on more firm footing for racial justice.

Herman Gray is Professor of Sociology at UC Santa Cruz and has published widely in the areas of black cultural theory, politics, and media. Most recently, Gray co-edited Racism Postrace with Roopali Mukherjee, Sarah Banet-Weiser.

Alondra Nelson, President of the Social Science Research Council and Harold F. Linder Professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, is an acclaimed researcher and author, who explores questions of science, technology, and social inequality. Nelson’s books include, Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination; and The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation after the Genome. She is coeditor of Genetics and the Unsettled Past: The Collision of DNA, Race, and History (with Keith Wailoo and Catherine Lee) and Technicolor: Race, Technology, and Everyday Life (with Thuy Linh N. Tu). Nelson serves on the board of directors of the Teagle Foundation and the Data & Society Research Institute. She is an elected Fellow of the American Academy of Political and Social Science and of the Hastings Center, and is an elected Member of the Sociological Research Association.

The event was co-sponsored by the UC Santa Cruz Institute for Social Transformation, the Science & Justice Research Center, NAACP of Santa Cruz County, ACLU Northern California Santa Cruz County Chapter, and Inner Light Ministries.

An announcement of the event appears in this campus news article.

Leading up to the event, SJRC Director Jenny Reardon and Herman Gray interviewed on race in America in January 2020 by Chris Benner (Director of the Institute for Social Transformation).

Rapporteur Report by Dennis Browe

“Racial Reconciliation and the Future of Race in America” brought together a group of three long-time friends and intellectual interlocutors for an intimate conversation with an overflowing audience at the Kuumbwa Jazz Center in downtown Santa Cruz. Jenny Reardon, who served as moderator, described how Herman Gray’s work on race in the media has been pathbreaking for many scholars, including Alondra Nelson. For a long time now, they have wanted to engage in conversation with Dr. Gray, and the recent formation of the Theorizing Race After Race working group presented a perfect opportunity to bring these three scholars together in dialogue.

The conversation included an array of themes including contemporary media; genealogy and genetic ancestry testing; reparations; our polarized nation; the term ‘post-racial’; and the status of the social sciences today. The three panelists discussed the challenges and opportunities of the present moment for understanding and creating social change around race, racism, and reparations in the United States, with the focus mainly on African American history and Black cultural studies. Framing the conversation and introducing the three panelists, Chris Benner, Professor of Sociology at UC Santa Cruz and Director of the Institute for Social Transformation on campus, referenced Michelle Alexander’s January 17 New York Times opinion piece, stating that with the urgency of this moment in our country’s history, “We don’t want to be in denial that the injustice of this moment is an aberration. Conditions of injustice have thrived throughout our history, as have the aspirational movements for and toward an inclusive democracy.”

Dr. Reardon began by asking a series of questions, with the conversation lasting about one hour, before opening it up to questions from the audience. The conversation centered around the expertise and most recent books of Dr. Gray and Dr. Nelson. Herman Gray recently co-edited a volume, Racism Postrace (2019), while Alondra Nelson recently published The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation After the Genome (2016).

Dr. Reardon launched the conversation by asking their thoughts about a new HBO show, The Watchmen, which brilliantly brings together and cuts across the panelists’ expertise: the relationships between science and technology – specifically genealogy and genetic ancestry – and race; and televisual media as a form of both social critique and speculative world-building. The Watchmen, based on the 1986 & 1987 graphic novel of the same name, takes place in an alternate-reality United States in which the U.S. won the Vietnam War, Nixon remained president for decades, and Robert Redford then assumes the presidency and oversees the passage of an act which provides reparations for descendants of victims of the Tulsa, Oklahoma Race Massacre in 1921. In this reimagined U.S., the passage of the pejoratively named “Redfordations” has sparked a backlash and uprising by white supremacists in Tulsa.

For the panelists, the show succeeds in leaving viewers slightly off-kilter; it scrambles conventional ways of understanding history and trauma, memory and subjectivity, particularly for African Americans. The show also scrambles temporalities: it plays with the possibilities of the past and prospects for the future, denying any clear narrative of progress from a more racist and unjust past to a more just present. For Dr. Nelson, the show succeeds in part because it is sci-fi: realism would not be able to capture the traumas of the past and their effect on memory and lived experience of African Americans that this show captures. It “Makes fun of the absurdity and profundity of racial violence… time gets snatched, people get snatched… The temporality starting and stopping is sometimes out of the control of marginalized communities.” However, the show is also of the horror genre for Dr. Nelson, as it deals with the genealogy of the Klan and the masking of everyone – superheroes, cops, white supremacists. The horror – the inability to know or not know who is a white supremacist – subtends the science fictional reimagination of the U.S. in the show.

The Watchmen also brings in real life Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who in the show plays the US Secretary of Commerce and guides African Americans in Tulsa through submitting DNA samples into a machine to find out whether they are eligible for reparations. This intersects with the work done in Dr. Nelson’s book who, through her ethnographic work with early African American adopters of direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic ancestry testing tools, investigated how and why people use genetic genealogy to make sense of their family’s history, especially in the contextual ‘afterlife’ of slavery and colonialism. Further, Dr. Gray made important connections between the entrepreneurial market logic of this show’s power and why television as a site of circulation is so fascinating: the ways in which memory and trauma attempt to gain cultural standing are tied in with the “marketability of the very idea.” Why, how, and when do certain cultural forms – such as African American trauma, historical but also lived in the ongoing present – become marketable to a mass television audience?

The conversation also touched on the similarities and differences between the Obama and Trump presidencies, with the theme of ‘postrace’ serving as a kind of touchstone which panelists repeatedly referred back to. For Dr. Gray and the co-editors of their Racism Postrace volume, their title does productive work by framing how proclamations of a postracial society further normalize racism and obscure structural anti-blackness. For Dr. Gray, “postrace is a kind of ideology of racism. It’s a set of ideas, dependent on race and racialization, about why race does or does not matter, in the aftermath of the Obama election.” However, postrace also marks the moment in which racializing logics and discourses are being challenged with a vengeance by mass social movements in the U.S.. Dr. Nelson also remarked on how the election of Donald Trump shattered any ideas about a clear teleological narrative of a ‘postracial’ U.S.: a “fantasy story that we told ourselves about race in this country. Now that’s been shattered, the spell has been broken.” Speaking about the case for reparations, for Dr. Nelson, Trump’s presidency has “moved us out of a space asking, is there something owed? Now the line is much more clear,” that something – reparations – is owed to African Americans.

When Dr. Reardon asked why reparations as a particular kind of racial politics have gained more prominence in this moment, referencing Ta-Nehisi Coates’s 2014 Atlantic article, “The Case for Reparations,” Dr. Nelson commented that for some communities reparations has always been at the forefront of their political consciousness and activities: “The question of now is really about a longer drumbeat that goes back to the nineteenth or even eighteenth century.” Why, then, did Coates’s article make such a splash, and why do reparations remain at the forefront of African American racial politics? For Dr. Nelson, reparations and what they represent are sufficiently polarizing: “The necessary conditions for a kind of white supremacist emergence, are the necessary conditions for a galvanizing around reparations. And that is just – the most extraordinary thing. Those polar energies bring it to the fore now.”

Perhaps even more importantly, for both Dr. Nelson and Dr. Gray, Coates was able to use his extraordinary talent as a storyteller to link the ‘everyday’ to the ‘structural.’ In his essay, Coates demonstrates how the legacy of structural economic racism – beginning with the Trans-Atlantic slave trade – gets carried forward into the future and impacts upon African American families and their everyday lives. Dr. Gray discussed how the ‘afterlife of slavery’ is tied into structural conditions – how wealth (or lack of wealth) is reproduced over generations: Coates demonstrated how even black families living in Chicago, who do their best to be ‘good citizens,’ who pay their rent and bills on time, find out after forty years of living there that they own nothing. They have not been able to build any wealth of their own.

The final two questions from Dr. Reardon asked about, first, the status of the social sciences today, and second, what hope in this moment might look like and where it might come from. Interestingly, these two themes converged and diverged in unexpected ways. Dr. Nelson, who is current president of the Social Science Research Council, replied that the social sciences need to become more nuanced in our thinking about historical change. We tend to think in terms of paradigms and periods such as the pre- and post-periods of agrarian and industrial revolutions and we tend to place temporal boundaries around historical events. However, in the world these historical events all interweave, both seamlessly and not. Thus, we must develop tools to become nimbler in thinking about how these historical events intermesh, not in a historical-additive model, but in a more dynamic, recursive mode of occurrence. It is not simply that we have been led to this current ‘neoliberal moment,’ but the important questions become: what do we mean by neoliberalism? What other forms of governance and political economy and historically racializing processes does neoliberalism coexist with?

Dr. Nelson also reminded us that while WEB Du Bois began his long career fully believing in the power of the social sciences to build objective knowledge that could tackle structural problems of inequality, by the end of his career he had become disillusioned and felt they were not up to the task of creating meaningful social change. However, for Dr. Nelson, this does not mean that we should lose hope in the social sciences. For her, the social sciences, even with their limitations, can help us think in nuanced ways around language and concepts used by scientists and by the public. For example, sociologists of science have been able to offer much nuance to geneticists surrounding the language they use to talk about race and racial categories. In what precise ways do race and ethnicity get used by geneticists, and how do these terms and categories confound or help clarify their experimental research? Sociology is primed to help think through these sorts of questions. Lastly, for Dr. Nelson, there is hope in social scientists finding a common purpose with other organizations and movements, working toward common goals to create social change.

Dr. Gray also provided an illuminating answer, simultaneously encompassing the limitations and the hope that may come out of the social sciences. He referenced Roderick Ferguson’s book, Aberrations in Black – which begins with a scene from Marlon Riggs’s experimental documentary Tongues Untied. In the scene, an African American person is walking around a lake – they perform gender as a woman but their sexuality remains ambiguous. Dr. Gray takes this example to do the work of what Dr. Nelson had just mentioned: “the capacity of the person exceeds social science’s ability to understand them.” This scene highlights the limits of representation and the troubles with normative categorizing that the social sciences highly value. If representation necessarily fails to a degree, and cannot fulfill its promises toward knowledge, the point then becomes acknowledging and working with excess – representational and categorical excess, and excesses of legibility. Dr. Gray wants to push social scientists to work in the space of these excesses, to trouble normative sensibilities of what gendered and raced subjects are expected to perform. He believes the social sciences are capable of doing this necessary work. In addition to social science, Dr. Gray himself turns to the cultural realm, specifically the sonic – music and imagination, jazz and blues – as a source of hope.

A running theme throughout the conversation, which I believe allows for an appropriate note to end this report on, concerned ‘the conditions of possibility’ which are necessary for social movements to arise and grow. Dr. Reardon quoted from an interview with black cultural theorist Paul Gilroy, who in the early 2000s believed that genetics would be a tool that allowed for the world to transcend race since human genomes are around 99.8% the same. Paul Gilroy in his interview admits that he was wrong about genetics but does not apologize because he was looking for hope, and he will continue looking. As the panelists discussed, how does hope structure conditions of possibility? What were the conditions of possibility through which Obama became elected, and through which Coates’s 2014 reparations article was able to make such a splash? And what conditions of possibility will become necessary for both narrow and mass social movements to flourish – ones which continue protesting police brutality such as Black Lives Matter and allied ones which focus on structural change of racist, political economic systems at the broadest levels?

This genre of question leaves the ending open-ended, a maneuver which resonates with the work of Ruha Benjamin, who recently presented her work at a SJRC event. Dr. Benjamin argues that in order to fight the growth of ‘The New Jim Code,’ including racializing technologies and algorithms, social movements need to intervene at the level of the imagination. I believe Dr. Gray and Dr. Nelson both argue for this too, finding hope in the social sciences and coming to the social sciences through other modes and mediums of hope. Both scholars’ work, along with Dr. Reardon’s, has and will continue to center on realizing the conditions of possibility for these imaginative interventions, so deeply needed to sprout and flourish across our shared world.