Hosted by David Theo Goldberg and UCHRI on Friday, June 05, 2020.

UCHRI gathered Angela Y. Davis (Emerita, UC Santa Cruz), Herman Gray (Emeritus, UC Santa Cruz), Gaye Theresa Johnson (UC Los Angeles), Robin D.G. Kelley (UC Los Angeles), and Josh Kun (USC) to think differently together about the structural conditions and explosive events shattering our times.

In a wide-ranging conversation emerging out of the national and international protests in response to yet another spate of anti-Black police violence, these leading critical thinkers engage questions about intersectional and international struggle, the militarization of the border, racial capitalism, the feminist dimension of new social justice movements, the unsustainability of the nation-state, the power of the arts as a rallying force for imagining and sustaining solidarities, and much more.

Rapporteur Report by Dennis Browe (PhD Student, Sociology, UC Santa Cruz)

Moderator

Herman Gray (Professor Emeritus, Sociology; SJRC Advisor, UC Santa Cruz)

Participants

Angela Y. Davis (Distinguished Professor Emerita, History of Consciousness, UC Santa Cruz)

Gaye Theresa Johnson (Associate Professor, African American Studies, UC Los Angeles)

Robin D. G. Kelley (Professor, African American Studies, UC Los Angeles)

Josh Kun (Professor and Chair, Cross-Cultural Communication; Director, School of Communication, University of Southern California)

The Fire This Time: Race at the Boiling Point (recording), which took place on June 5, 2020, brought together a superb collection of scholars to think together about this powerful moment – a confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ‘fed up’-risings against police brutality and systemic racism taking place across the U.S. and globally. Hosted by the University of California Humanities Research Institute (UCHRI), over 9,000 people joined, indicating the energy of the moment and the hunger that so many have for real change and more justice both in the U.S. and abroad.

David Theo Goldberg, director of UCHRI, introduced the event and set the tone by noting the pain but also the hope engendering the circumstances of this necessary conversation. Dr. Goldberg also acknowledged the UC Santa Cruz wildcat strike and larger UC graduate student struggle for secure living wages still taking place, linking the militarized police suppression of the strikes across numerous UC campuses (though especially the UCSC picket line) to the police repression we are seeing on the streets across the U.S. today. Directly connecting the COLA movement with the reason for this event, he stated: “The impacts [of disciplinary measures taken by administration] have fallen especially hard on students and faculty of color.”

Herman Gray served as the moderator of the panel. Repeating a powerful Black Lives Matter mantra, he began by individually naming those most recently killed by police: “Of course, we are here because of the public lynching of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and David McAtee.” Much of the conversation centered around the transformative power of this moment and the types of hope that have been opened up. Panelists used a number of metaphors and analogies, borrowing other scholars’ words to describe these affective openings in the body politic. Gray relayed Antonio Gramsci’s phrase “the pessimism of the intellect and the optimism of the will” to speak about opportunity in crisis, while Stuart Hall’s notion of this being a truly ‘conjunctural moment,’ full of possibilities, was also invoked. Additionally, Angela Davis mentioned Arundhati Roy’s recent writing on the novel coronavirus as a ‘portal’ that can lead to something new, something different.

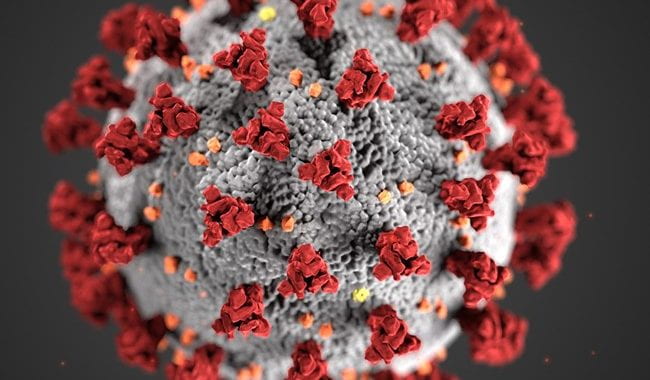

Gray then pulled on the polyvalent slogan, “I can’t breathe” to link together a number of intersecting structural conditions that harm Black and Brown people. These conditions literally affect their ability to breathe, while breath also metaphorically stands in for conditions of the measure of the good life. First, it is often poorer Black and Brown communities that have to live near polluted environments and polluted air. Second, the devastating health impacts of COVID-19 are hitting Black and Brown communities the hardest – importantly, not due to ‘racial’ genetics but due to structural racial inequalities, such as socioeconomic status and living in dense, low-income housing. And third, this phrase has been engrained into national consciousness by a number of Black men – Eric Garner and George Floyd as just the two most well-known names – who whispered these final words through their constricted airways under the weight of police chokeholds and knee-holds. “I can’t breathe” captures this confluence of structural conditions that for Gray opens a space to think through this moment and the possibilities for real change.

The panelists recognized that, while powerful, ultimately this hopeful moment will not last, and a main question becomes what people can do next, how to move in the direction of a better future. Gaye Theresa Johnson offered keen insight here by saying that when people ask what we can do next, they are thinking within institutions; instead, what we need is a fundamental shift around our notion that what we need is a leader (usually a man) to tell us what to do and where to go next. She stated: “we need to start doing this ourselves,” by starting conversations and sometimes simply listening to and supporting the people already doing this work. Johnson remarked on signs of hope coming from these uprisings: they are teaching us “a different kind of calculus of human worth,” one predicated on the inherent humanity of Black and Brown people, who deserve to be here simply because they are breathing, able to draw breath. The suffering, she said, of Black and Brown and trans people, is met with skepticism, putting the burden of proof on them over and over again in order to have to prove their humanity. However, it is through and in struggle that “we always have the lessons of what we need in order to become free.” Davis also referenced the 2015 uprisings against white supremacy at the University of Missouri, reminding us that while the intensity of that powerful moment did die down, it is vital to not lose sight of the openings created for systemic change, even if it is difficult to not see immediate results.

Robin D.G. Kelley noted that there has long been an ongoing war that preceded COVID-19 – a war against poor Black and Brown communities which includes preexisting conditions of racism and structural inequalities. Referencing Cedric Robinson – his teacher and teacher to many on the contours of racial capitalism – Dr. Kelley linked together a number of phenomena into this ongoing war: exacerbation of border closings and horrible conditions of immigrant detention centers; bypassing of labor laws by Amazon, Instacart, and other gig workers; the deeply unsafe conditions of working in the meatpacking industry; as well as the growth of authoritarian regimes all over the world. These interlinked phenomena are manifesting in the unequal effects of COVID-19 and this most recent set of murders by law enforcement, all laying bare the intensity and the possibilities of the current struggle to live collectively. As Jenny Reardon, Professor of Sociology and Director of the Science & Justice Research Center at UC Santa Cruz, argues in a recent essay, it is veracity – ‘trustworthy truths’ – that is required to help imagine and create a more just world, centered around recognizing our collective relations with others.

Josh Kun picked up on this thread, discussing the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border by highlighting the converging effects of policing Black and Brown bodies in this country, including how Homeland Security and ICE have become further integrated into domestic functions of policing (even as far back as 1992, the U.S. Border Patrol was used in Los Angeles to ‘clean up the streets’ and deport Latinos). Kun then discussed his work following Richard Misrach, an influential photographer who documented the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border during the Obama administration. Misrach found all sorts of white supremacist spray paint messaging across the border rocks: “These linked systems of hate and terror are actually written on the walls, written on the landscape and on the land that has been stolen.” While the fear and hatred of Latinx immigrants is so palpable for many in this country, Kun took this opportunity to remark that the strong networking of how domination and violence happens needs to be met with the same level of resistance networking, the same level of strength of convergence and coalition-building.

After the initial round of commentary, the conversation turned to the importance of a global perspective and the need to confront ongoing racial capitalism since, as Angela Davis reminded us, racism is not just a domestic problem. Importantly, the importance of a broad internationalist, solidarity-based perspective turns on the need for awareness of the limitations of the nation-state. The panelists all seemed to agree that, as Davis stated, “the nation-state as we know it is no longer possible.” The liberal nation-state, which, even with its short history in the U.S. (Kelley remarked that the social-democratic liberal U.S. state only appeared during Reconstruction and did not last long) has been hollowed out and dominated by market-based, neoliberal ideology. For the panelists, this is where the authoritarian regimes come in to maintain control of the nation-state – capital still needs to be allowed to freely cross borders, but these regimes use nationalist surges and fear tactics to gain followers. Johnson remarked how these authoritarian nationalist surges are not just a demonstration of power but are also a measure of white supremacy’s fragility. She pointed to a material metaphor to symbolize this white fragility by noting the flimsy chain-link fence that has been put up around the White House to keep protestors out: “It’s the narrative, the gesture that you are not welcome, this is our house. But it’s a permeable chain-link fence, it’s not going to keep anybody out or in.”

The internationalist movement that has exploded across the globe is laying bare this white supremacist fragility, and the beauty of this new movement (which builds on but goes beyond work done by Occupy and on Black Lives Matter struggles over the past decade) is that is a coalescence of contesting anti-Black and anti-Brown state violence. Davis noted that when we say ‘abolish prisons’ and ‘abolish the police,’ we are thinking about a future in which we have moved beyond the bourgeois notion of the nation-state (which is constitutively anti-Black). Johnson beautifully remarked that the nation-state does not, and cannot, “hold all of the dreams and imaginings that we have for our communities, that we have in our own time… we have our own ideas about what freedom is…We are so infuriating to the authoritarian fascists because [we call] their bluff. We refuse their world because we have a whole different set of imaginaries that they cannot even comprehend, and these are ready to be enacted.”

Gray, in a way linking these alternate imaginaries of another world to the question of care – of taking care of one another in the streets through mobilization and protest – noted that this has been an essential element of these uprisings. Davis responded by asking, “Who usually does the care?,” conveying the importance of recognizing the feminist dimension of these new movements. Kelley then echoed a critique being made often this past month: why do police have all the equipment they need, but healthcare workers cannot get enough personal protective equipment (PPE)? This discrepancy speaks to the overfunding of the masculine-imperialist police force and the underfunding of more feminized healthcare work.

After Kun’s discussion of the importance of cell phone video footage of racialized police brutality as producing a ‘new archive of truth,’ Gray introduced questions from the audience, covering topics including building multi-racial coalitions and organizing; the small-scale steps that people can take as well as what changes institutions need to make; and COVID-19’s economy of violence whereby we are seeing a shutdown of the economy and hundreds of thousands of deaths at the same time that there has been a massive distribution of wealth to the super wealthy. Panelists discussed structural issues that have become exacerbated during the pandemic such as the privatization of healthcare and the mainstreaming of corporate care about issues of anti-Blackness (See, for example, statements put out by Coca Cola and by 23andMe; as well as UC Press’s statement supporting Black Lives Matter). Kun highlighted how corporate maneuvers, which put out public, surface-level statements supporting Black Lives Matter while changing none of their own policies which contribute to racial inequalities amongst their workers, can actually increase capital accumulation on the backs of Black people.

The final part of the conversation revolved around the power of music and visual art as part of freedom struggles. Especially in this moment of isolation from COVID-19 quarantine as it has run up against the uprisings, the sonic dimension of sociality has become even more important. Davis remarked how one of the reasons why people all over the world are drawn to the Black struggle in the U.S. has to do with the power of Black music: along with the Black music that has traveled have been the stories of Black resistance. And this, she thinks, is one of the reasons why there is not nearly the same level of global solidarity with other freedom struggles such as of the Palestinians and Kurds. However, music has the power to open up solidarities across struggles.

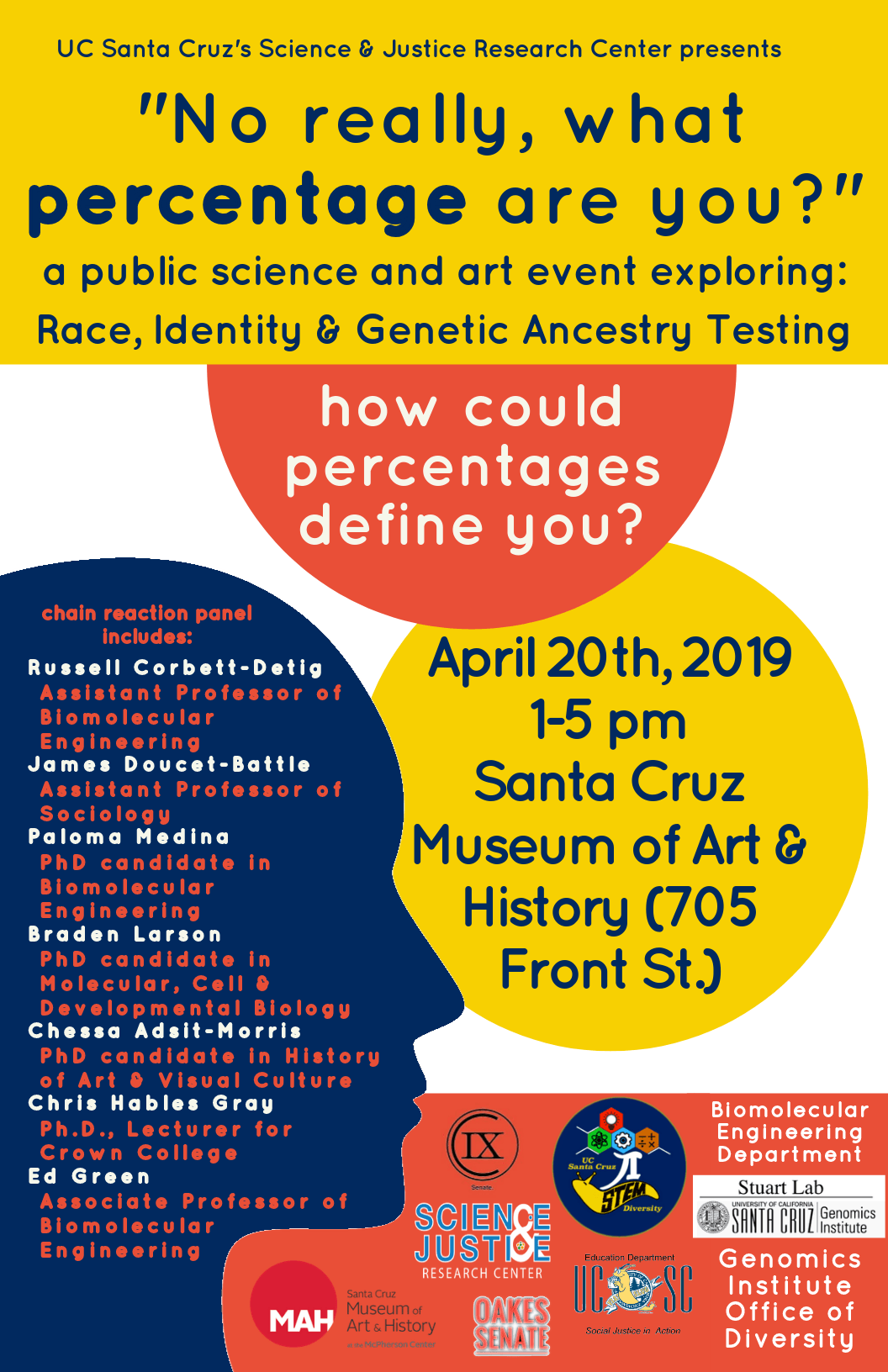

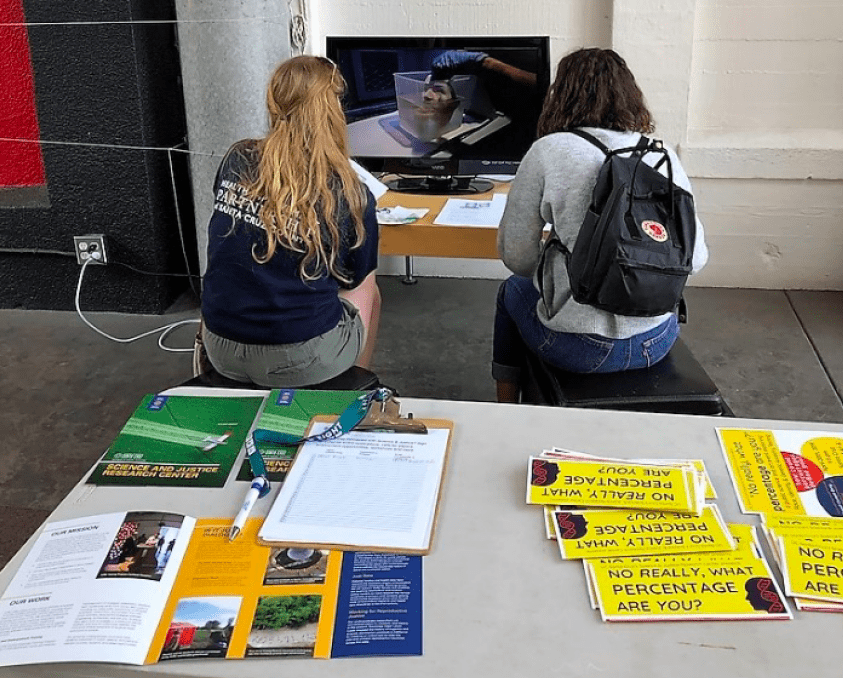

Fittingly, this past January the Science & Justice Research Center (SJRC) co-hosted an event on the future of race in the U.S. (which was a conversation between Herman Gray and Alondra Nelson, with Jenny Reardon serving as moderator); the ongoing theme of that conversation centered around how to realize and create conditions of possibility for transformative social moments/movements. And now, just five months later, a massively transformative moment has arrived in full force, opening up new possibilities for taking action centered around a more expansive notion of freedom and for thinking about what work remains ahead.

I end with a comment from Kelley, based on an audience question asking how to reconcile two timelines of freedom: the freedom enshrined in the U.S. Constitution on the one hand, and on the other hand the fact that many groups such as Blacks still do not have that full freedom. He replied by remarking that these are not two separate timelines, since they are dialectically related. One freedom is dependent on the other: unfreedom. For whites in the U.S., their freedom has always depended on the unfreedom of others. Taking in and digesting the wisdom of these scholars pushes us to continue thinking through this powerful moment, envisioning how to build more livable presents and more just futures. Since freedoms are dialectically interdependent, this moment, however short-lived, offers a chance to think and act our way out of the differentially deadly contours of racial capitalism, imagining life-giving alternatives to the conditions of anti-Blackness that can transmute “I can’t breathe” into something like “We breathe better, beautifully together.” This will take massive work on a broad internationalist scale and is prone to opposition and counter-forces at every step along the way, but as this conversation showed, this moment of transformation is already here as an ongoing new beginning.